It may be a bit early in springtime to be nominating an Album of the Year, but I’ll be very surprised if any release in the next eight months makes me sit up and take note with such awe and excitement as this absolute cracker from the Dutch label Pentatone. The composer turned 99 two months ago. He has been writing this piano series – the Hungarian title means ‘Games – since 1973, adding fresh episodes every now and then. There are 75 complete movements to this suite and another ten in manuscript. Kurtág may yet have more up his…

Browsing: Lebrecht Weekly

The most influential Irishman in the history of music is not Bob Geldof, Bono, Sinead O’Connor or the Dubliners, all of whom are famous as influenza, but a fairly obscure piano salesman who awoke a sub-continent to its creative potential. John Field was born in Dublin in 1782 to Anglican parents who took him to London to work for Muzio Clementi, Beethoven’s publishing partner and piano dealer. As a rep for the wealthy Clementi, Field travelled to Paris and Vienna before settling in St Petersburg, where he starred at the new-founded Philharmonic Society. Field gave three piano lessons to Mikhail…

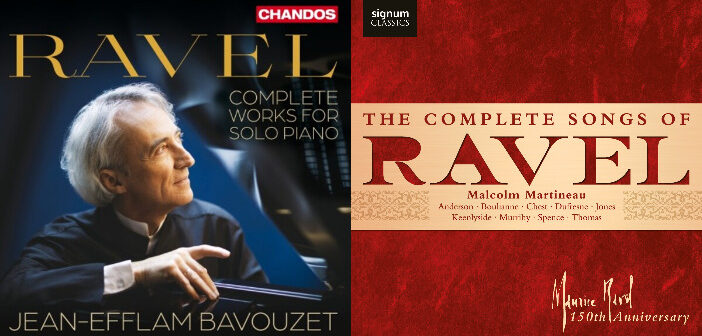

Both double-album titles left me feeling uncomfortable. Ravel is a miniaturist, a maker of exquisite small things that drop into your consciousness like olive oil into a bowl of rice. Each drop is an object entire. Pour them freely and the uniqueness dissolves. It speaks volumes for both of these projects that they manage to avoid that danger, most of the time anyway. Jean-Efflam Bavouzet takes a chronological route, starting with a Serenade grotesque written in 1892 when Ravel was 17 and concluding with that monstrously grotesque caricature of morbid Vienna known as La Valse (and more often heard in…

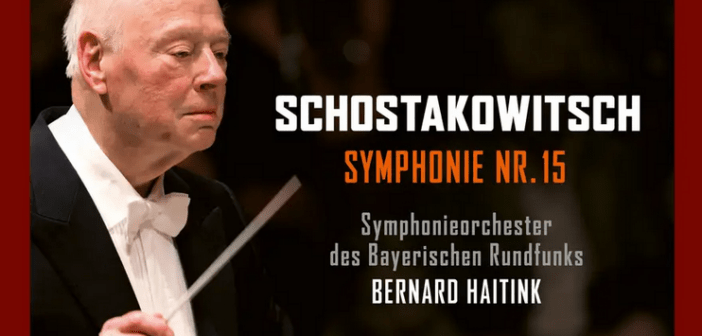

Dmitri Shostakovich wrote his last symphony with left hand alone. A heart attack in 1966, followed by several falls and fractures, left him heavily disabled. His solution was to train one hand to do the work of two and economising on physical effort. This may explain the expanses of blank staves in some pages of his fifteenth symphony, as if he lacked strength to fill in instrumental detail. Maxim Shostakovich, who conducted the 1972 premiere, called the work his father’s ‘birth-to-death autobiography’. That, too, is only a partial view. The symphony opens with a holiday funfair and a blast of…

I love artists who attempt the impossible. Within reason, that is. I’d draw the line at someone playing the 32 Beethoven sonatas one-handed, or the 15 Shostakovich quartets without a bathroom break. But any artist who takes a piece of music beyond the limits of what I’d heard in it before gets my vote. The American cellist Zlatomir Fung has composed a fantasy on Janacek’s opera Jenufa, a feat that defies credibility. The tunes and rhythms of Jenufa are rooted in Czech speech patterns. Erase the voice, and what’s left? An X-ray. Fung and his pianist Richard Fu present fifteen…

Many composers have tried to improve on Schubert. Mahler made a string-orchestra version of the Death and the Maiden string quartet, Joseph Joachim orchestrated a four-hand piano sonata, Liszt made the Wanderer Fantasy into something resembling a piano concerto. Even atonal Anton von Webern had a go. All with the best of intentions and without harm to the crystalline original, but you do wonder what value they added. Schubert, like apple strudel, does not need sweetener. What we have on this album are little-known orchestral settings by famous composers of four perfect songs. Benjamin Britten tacked on two clarinets and…

In a world of mounting uncertainty, it’s a relief to find the King’s Singers are still around. The novelty of their act might have worn off since that inaugural London concert in 1968 but polished a capella singing by six male voices remains a miraculous thing and their latest album is a joy to spin. The title is Shakespeare – The Tempest Act 4 (but you knew that, surely) – and the underlying theme is the hope we cling to in times of mortal terror. Three Vaughan Williams songs from 1951 capture that dichotomy to the depths of its poignancy.…

The English conductor Sir Eugene Goossens was stopped in March 1956 on arrival at Sydney Airport. He was found to be in possession of pornographic materials and rubber goods that he intended to share with a female lover. The police had been tipped off by a tabloid reporter, in cahoots with the conductor’s professional rivals. Goossens was fined a hundred pounds and left Australia in disgrace. Back in London he resumed working with BBC orchestras and others, going on to make one of my most-played recordings, the Bach double concerto with the Oistrakhs. Sir Eugene, who kept his knighthood, died…

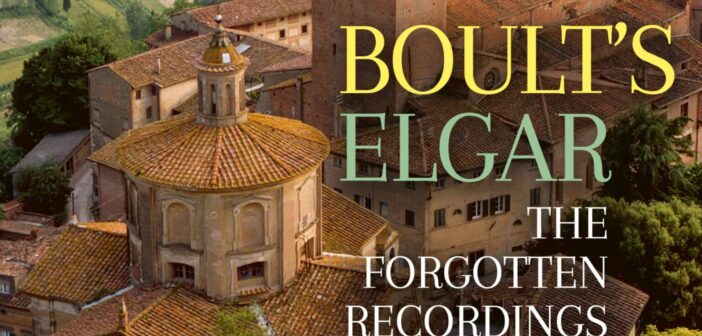

There are days when only Elgar will do. When the skies are low and the politics grim, a wash of Elgarian orchestral colour relieves existential gloom like no other remedy. The first symphony delivers pull-your-socks-up bluster and the second a subtler encouragement. Elgar always does it for me. This extraordinary double-album, titled Boult’s Elgar, brings together unpublished recordings by the composer’s young friend, Sir Adrian Boult. The sleeve notes are by Nigel Simeone, whose new book, Edward Elgar and Adrian Boult, chronicles a friendship that was interrupted for seven years by the composer taking umbrage at something the conductor had…

The Egyptian soprano, based in London and Berlin, had a mix of western and Arabic classical songs on her debut album, illustrating musical connections around the Mediterranean. Her ease in both ethnicities was enviable. To change tracks from microtonal maqam precision to the lushness of Ravel’s Shéhérazade was a hair-raising act of cultural transcendence, achieved without a hair out of place. Fatma Said’s new album is pure German: Schubert, Mendelssohn, Schumann and Brahms. Hard to tell which she adores most. The opening track, ‘Ständchen’, has an arresting liquidity, only to be outshone by ‘Auf dem Wasser zu Singen’. Felix Mendelssohn’s…