Based on Die Letzte am Schafott (“The Song at the Scaffold”), a novella about the execution by guillotine of sixteen Carmelite nuns from Compiègne in 1794, Georges Bernanos (1888-1948) wrote a screenplay for a film that ultimately was not produced. However, seeing its potential, Italian publisher Ricordi bought the rights and commissioned Francis Poulenc to write Dialogues des Carmélites, based on Bernanos’s work. The opera premiered in 1957 at La Scala to great acclaim, and has been a mainstay of the twentieth-century opera canon ever since.

In Act I, Blanche de la Force, a young noblewoman afflicted with an unnamed pathological fear, decides to enter a Carmelite convent. The old Prioress informs Blanche that the convent is not a refuge; it is the duty of the nuns to guard the Order, and not the other way around. On her deathbed, the Prioress, worried about Blanche, entrusts her care to Mother Marie. The Prioress dies an agonizing death, witnessed by Mother Marie and a shaken Blanche.

In Act II, the Chevalier de la Force, Blanche’s brother, is worried for her, due to the anti-clerical tide sweeping revolutionary France, compounded by her aristocratic status. He implores Blanche to move to a safer location, but she refuses, asserting she’s found happiness in the Carmelite order. A policeman arrives to inform the nuns the convent has been nationalized and will soon be auctioned. They’re told they must give up their religious habits and renounce their vocation.

In Act III, Mother Marie proposes the nuns take a vow of martyrdom. There’s one dissenting vote: young Sister Constance. A terrified Blanche escapes to her family home to discover her father has been guillotined, and she is forced to serve her former servants. The nuns are arrested and condemned to death while Mother Marie is absent, searching for Blanche. Eventually found, Blanche refuses to join the other nuns. But in the final scene, as the nuns are guillotined one by one, Blanche joins them, singing the sacred voluntary promise of the religious order, literally offering themselves to the Lord.

Doris Soffel (Old Prioress) & Michèle Losier (Mère Marie) in Palau de les Arts Reina Sofía, Valencia’s Dialogues des carmélites. Photo: Miguel Lorenzo-Mikel Ponce/Les Arts

Amazingly, this was the debut performance of this decades-old opera in Valencia (seen Jan. 28). What better way to present the work to a new public than Canadian director Robert Carsen’s production? His Dialogues des Carmélites originated in Amsterdam and has toured the world’s great opera houses—Milan, Vienna, London, Madrid, Chicago and Toronto—to deserved acclaim.

Thanks to Michael Levine’s minimal sets, the drama is taut and intense. The opening scene in de la Force’s palace consists of an elegant fauteuil on which the Marquis is seated, surrounded by valets, under a grand chandelier. By his masterful understanding of lighting, Cor van den Brink brilliantly created a magnified shadow theatre. Blanche is terrified by the looming shadow of her valet just as she is petrified of life in general.

Poulenc managed to create distinct personalities for the five major characters: Sister Blanche, Sister Constance, Mother Marie, the old Prioress and Madame Lidoine, the new Prioress.

Ambur Braid (Madame Lidoine) in Palau de les Arts Reina Sofía, Valencia’s Dialogues des carmélites. Photo: Miguel Lorenzo-Mikel Ponce/Les Arts

French soprano Alexandra Marcellier was an incandescent Blanche, personifying the noblewoman’s fear from her first moment onstage. Sister Constance, another novice, was sung by the Franco-American singer Sandra Hamaoui. She is Blanche’s lighter alter ego, a country girl imbued with joie de vivre. Hamaoui’s agile, bright coloratura contrasted beautifully with Marcellier’s lyric soprano. German mezzo Doris Soffel, a leading Rossini and Mozart mezzo decades ago, was the old Prioress. She managed to convey the fear of death that even devout nuns must suffer. Soffel impressed with her magnificent acting, though her voice at times showed signs of strain.

Ambur Braid hails from British Columbia, yet her diction was impeccable. A few months ago, Braid was a remarkable Rachèle in Halévy’s La juive in Frankfurt, where she astounded with her singing, acting and diction. She was this production’s Madame Lidoine, the new Prioress. Thanks to her expressiveness and winning charisma, she was magnetic from the start.

Another Canadian, Michèle Losier, was a touching Mother Marie. This exceptional mezzo performs leading roles in the world’s major opera houses. Last season, I was impressed by her Octavian in Christoph Waltz’s magnificent production of Der Rosenkavalier in Geneva. Thanks to Losier’s expressive acting, Mother Marie had a powerful presence.

The three male roles were well sung and acted. French bass Nicolas Cavallier was a noble and kind Marquis de la Force, Blanche’s father. A rising tenor on the French opera scene, Valentin Thill, was an effective Chevalier de la Force, Blanche’s valiant brother. When the Chevalier comes to the convent to bring his sister to safety, she refuses. Carsen’s staging for this scene was electrifying: a row of veiled nuns stood between the two siblings to express the growing distance and Blanche’s attachment to the Carmelites. Irish-Canadian tenor Michael Colvin played a touching chaplain of Carmel. He avoided overdoing the role’s pedantry and soberly conveyed the role’s necessary humility and compassion.

It’s truly impressive the pervasive Canadian talent now found on the stages of European opera houses. Director Robert Carsen and three of the singers in this production hail from this nation, truly a source of pride and joy.

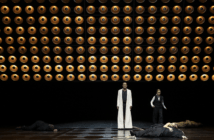

Alexandra Marcellier (Blanche de la Force) and Ensemble in Palau de les Arts Reina Sofía, Valencia’s Dialogues des carmélites. Photo: Miguel Lorenzo-Mikel Ponce/Les Arts

The Cor de la Generalitat Valenciana sang in idiomatic French, no minor feat. The chorus, supplemented by extras, played a major role in the production. They often appeared between scenes at the front of the stage, enabling seamless scene shifts. They were terrifying as the revolutionary populace when they entered the convent with the police. By closing in on the nuns as a collective human wall, they invoked a claustrophobic terror.

The Orquesta de la Comunitat Valenciana under Riccardo Minasi was able to bring out the marvellously rich palette of colours in Poulenc’s intricate score.

Carsen’s staging of the finale was majestic, and infinitely more effective than the conventional marching of the nuns to the guillotine, mercifully not shown. Instead, the sixteen nuns are artfully arranged in a tableaux. With each guillotine sound, a nun falls. When only two remain, Blanche rushes in to join her martyred sisters. As Hitchcock proved, the unseen is scarier than the seen.

For more on the opera and concert season at Valencia’s Palau de les Arts Reina Sofía visit www.lesarts.com