Bellini’s final opera, I puritani (1835), premiered shortly before the composer’s untimely death by accidental poisoning. It is one of the highpoints in the romantic Italian bel canto repertoire, leaving us to wonder what other masterpieces Bellini might have written had he lived past thirty-three.

I puritani is based on the French play Têtes Rondes et Cavaliers (1833), itself derived from Sir Walter Scott’s Old Mortality (1816). It takes place in Plymouth circa 1640, during the English Civil War fought between Puritans and Royalists culminating with Cromwell’s victory.

Reputed to have been Queen Victoria’s favourite opera, it’s dramatically compact and replete with gorgeous melodies. Less elegiac than La sonnambula (1831), it’s basically a duet between virtuosi, tenor and soprano, with occasional accompaniment from bass and baritone. The challenge in producing it is in booking the appropriate singers, especially the tenor and soprano. This is why it’s performed less frequently than La sonnambula or Norma (1831).

Lisette Oropesa (Elvira) in Paris Opera’s I puritani. Photo Sebastien Mathe

Many attending on opening night (Feb. 6) were obvious fans of Cuban-American soprano Lisette Oropesa. Her lyric coloratura easily met the demands of the role, but her first scene was somewhat tentative. There were moments of sharpness, but happily matters improved. Director Laurent Pelly’s vision for Elvira was of an extremely fragile young woman who had difficulty coping with the political events around her. Oropesa put a lot of energy into the dramatic interpretation, which may have affected her vocal performance. Even in moments where Elvira didn’t sing, she was agitated, not unlike an incarcerated mental patient.

This had a negative dramatic effect overall, as this unending manic behaviour is impossible to sustain over several hours. The “mad scene,” Act II’s “ Qui la voce sua soave,” lost its effect, as it was but one episode in a relentless display of instability. Nevertheless, Oropesa was at her best here, as well in Act I’s moving finale, “Vieni al tempio.” Thanks to her impeccable phrasing and invaluable support from conductor Corrado Rovaris, this was the evening’s most haunting moment.

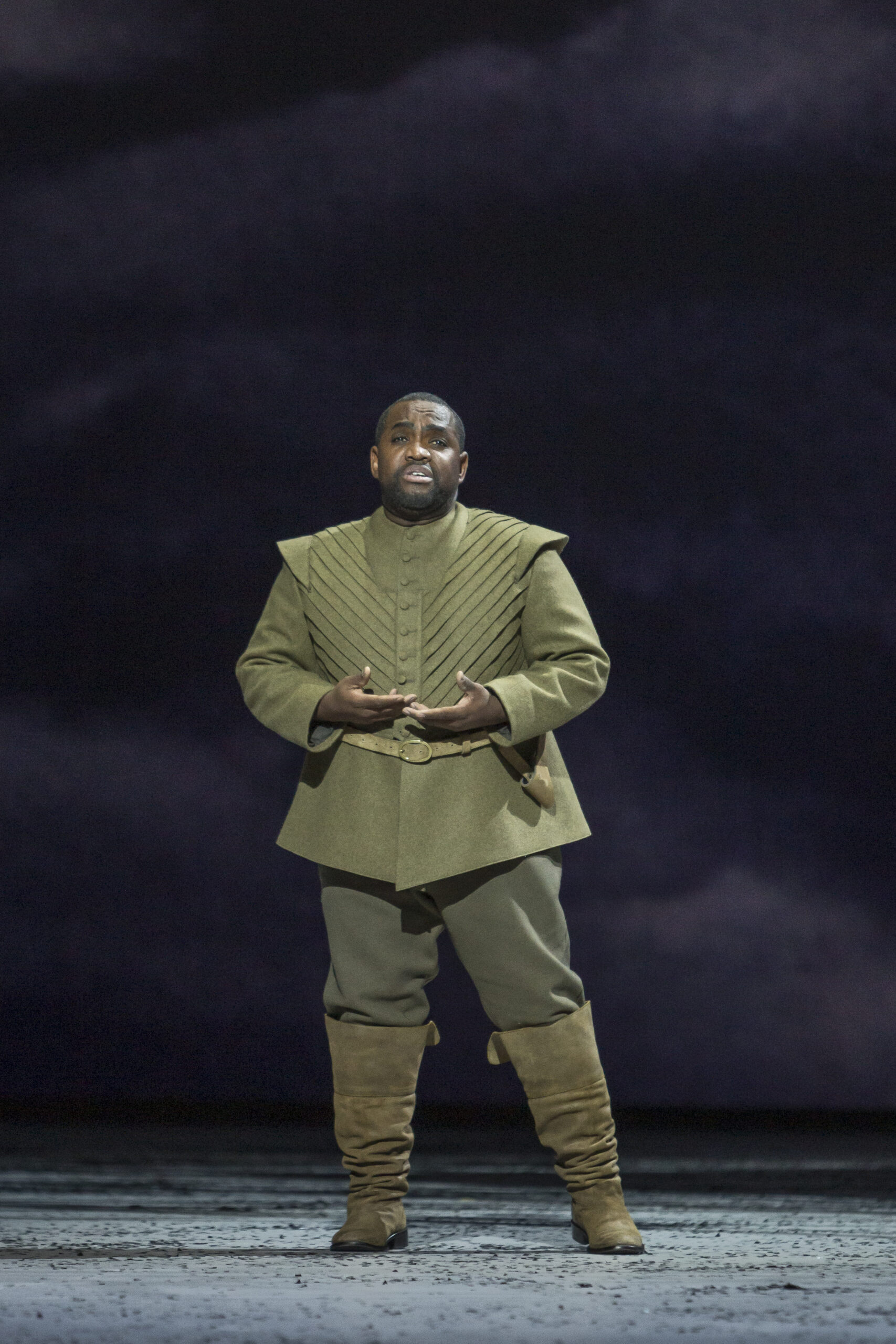

American tenor Lawrence Brownlee’s voice was too small for the role of Arturo. He was able to emit the high notes (or at least most of them) but his timbre is not the most appealing, and his accutti sometimes felt forced. He was at his best in Act I’s lyrical “A te o cara,” and least effective in Act III’s demanding passage “crudeli, crudeli! Ella è tremante, ella è spirante; anime perfide, speed a pietà!” For this punishing number, Bellini wrote a high F-natural above high C. Instead, Brownlee transposed the F to a D to underwhelming effect.

Despite his limitations, Brownlee had more success than baritone Andrei Kymach as Riccardo. He was the 2019 first prize winner in BBC Cardiff’s Singer of the World Competition. That was six years ago, but as evidenced on Feb. 6, the Ukrainian displayed a powerful and dark voice but his style was a long way from bel canto, and his diction incomprehensible.

Lawrence Brownlee (Arturo) in Paris Opera’s I puritani. Photo: Sebastien Mathe

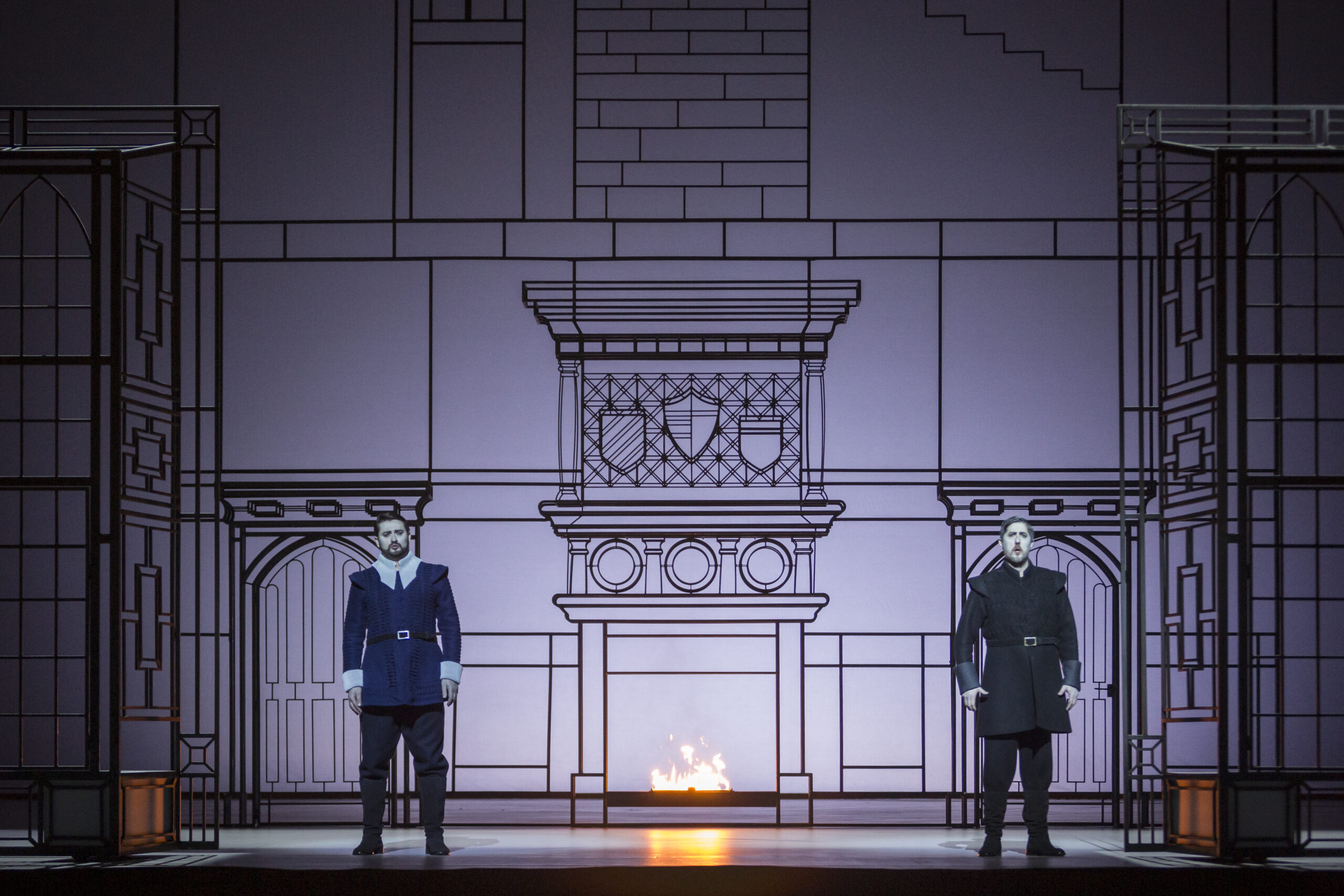

In stark contrast, the evening’s most beautiful singing was from Roberto Tagliavini, as Giorgio, Elvira’s uncle. Act II’s “ Il rival salvar tu déi, / il rival salvar tu puoi… Suoni la tromba,” is one of Italian opera’s greatest bass/baritone duets. Here, Kymach’s shortcomings were augmented when juxtaposed with Tagliavini’s velvety, polished bass and exemplary diction.

The smaller roles of Enrichetta, Gualtiero and Bruno were given to members of La troupe lyrique de l’opéra national de Paris. Young Dutch mezzo Maria Warenberg was an effective Enrichetta, regal in posture and a credible queen, albeit deposed. Her timbre was warm and pleasing in her scene with Arturo (“Non parlar di lei che adoro, / di valor non mi spogliar”) that precedes Elvira’s joyful polonaise (“Son vergin vezzosa”). Young Canadian bass-baritone Vartan Gabrielian was an elegant Gualtiero. His voice was powerful and his stage presence imposing. It’s a pity Bellini didn’t write more for Gualtiero to sing.

The chorus, pivotal in Bellini’s operas, was effective, though the staging rendered them awkward, possibly the director’s intention, to insinuate the rigidity of the Puritans.

Pelly’s choice to make Elvira mentally troubled from the onset was misguided. Other than exhausting Oropesa with histrionics throughout, in a work already demanding much concentration, it added nothing to the enjoyment or understanding of the work. Dramatically, it reduced the intensity of the mad scene, as it’s more disturbing to see a healthy, joyous Elvira sink into mania than to endure nearly three hours of her unending madness.

Pelly’s sets consisted of a metallic structure representing an English fortification. Its sharp edges and linear design were intended to represent the Puritans’ austerity, as were Chantal Thomas’s drab grey and black costumes. In contrast, Elvira’s white dress represented innocence. During the second act, when Elvira goes mad, the metallic structure folds into a rectangular tower to which she is confined. Once again, Elvira’s histrionics were a distraction where the spotlight should have been on Bellini’s superlative vocal passages.

Andrei Kymach (Riccardo) & Roberto Tagliavini (Giorgio) in Paris Opera’s I puritani. Photo: Sebastien Mathe

Poet Felice Romani (1788-1865) was the librettist for most of Bellini’s operas. For I puritani, Bellini resorted to Carlo Pepoli (1796-1881), a revolutionary poet-in-exile based in Paris, where Bellini then resided. It was Pepoli’s first libretto, which may explain its weakness. For example, the concept of Arturo escaping with Queen Enrichetta on his wedding day to save her from a doomed fate could have been better portrayed and justified. The sudden pardon of Arturo after the defeat of the Stuarts is also rather abrupt.

Pelly’s staging was not able to mend the plot’s weaknesses. This may be why he opted for a novelty: when Elvira reconciles with Arturo and supposedly regains her sanity, she collapses. This is how Pelly’s I puritani ends! It appears that she dies, though an optimist might surmise she merely faints. In either case, this choice only accentuated the opera’s biggest weakness (its libretto).

Opéra national de Paris’s I puritani continues its run at the Opéra Bastille through March 5. www. operadeparis.fr