Nothing is less hip than a strenuous attempt to be hip. This is how polite society would describe Paul Sellars’ take on Rameau’s Castor et Pollux (seen Feb. 7). I’ll leave it to your imagination how less charitable souls would describe it, or you might prefer to check your social media.

The story of Castor and Pollux is somewhat reminiscent of Orpheus and Eurydice but with fraternal love instead of marital love as the motivation. Castor and Pollux are twin half-brothers born to Leda. Castor was her son from Tyndareus, King of Sparta. Pollux, an immortal demi-god, was her son from Zeus, who seduced Leda in the guise of a swan. Both brothers are in love with Princess Télaïre who only loves mortal Castor. Both fight Lynceus, King of Thrace, and Castor is killed. Pollux in turn confesses his love to Télaïre, who does not reciprocate. She implores him to convince his father Zeus to resurrect Castor from the dead. Pollux visits the underworld to retrieve Castor, but if successful, he must take his place. Castor refuses the swap but accepts visiting the land of the living for one day to console Télaïre. Touched by the brothers’ love of one another, Zeus bestows immortality on both siblings.

Usually, Castor et Pollux is presented in its 1754 version, which replaces the Prologue with an act that makes the plot clearer and the action more compact. The present production is the 1737 original (and dramatically weaker) version. Apparently, the reason for this odd choice is that the earlier version’s allegorical Prologue refers to the Peace Treaty that marked the end of the War of Polish Succession (ratified a year later at the Treaty of Vienna). Laudably, the director is emphasizing an anti-war message. However, few would have guessed it had they not read Sellars’ programme note.

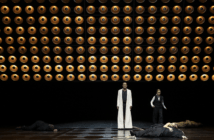

Jeanine de Bique (Télaïre) & dancer in Opéra national de Paris’ Castor et Pollux. Photo: Vincent Pontet

Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764) was an innovator and a prodigious composer. Given the tastes in his time, also France’s heyday, his operas were an aesthetically pleasing blend of opera and ballet. The latter is exquisitely elegant and refined. I cherish memories of Rameau operas presented by Toronto’s Opera Atelier that blended the two idioms, and a glorious Hippolyte et Aricie (1733) at Palais Garnier in 2012. Perhaps my anticipation of a similar experience added to my disappointment with this performance.

In the present production, the period is transported from antiquity to the present day. One hoped for a coup de génie, as in the Marcel Camus film Orfeu Negro (1959), a retelling of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice in a favela of Rio de Janeiro during Carnival. Unfortunately, one had to endure hours of breakdancing by supposedly hip people that was so tedious it made Götterdämmerung seem like a short interlude. Sellars transposed the action to an urban setting, specifically of gang wars. The opposing sides revel in breakdancing throughout. As hard as I tried, I couldn’t detect any relation between their street jiving and Rameau’s rhythms.

In general, I prefer innovative stagings to stale ones, especially when the director is both knowledgeable and creative, like a Robert Carsen or Damiano Michieletto. Artists like these possess a vast knowledge of history, mythology and literature and can connect the plot with other events, whether historic, present-day or literary. A competent director can draw parallels that in turn enhance and inform the opera. However, simply transposing Tosca to Qatar, La bohème to the moon or Eugene Onegin to a submarine are decisions that ultimately ring hollow beyond their initial novelty.

Stéphanie d’Oustrac (Phébé) in Opéra national de Paris’ Castor et Pollux. Photo: Vincent Pontet

It would seem Sellars wanted to shock and disturb—and that he certainly did. By moving a story from Greek Antiquity to a modest apartment in the Bronx, he was able to offer the public a spectacle of street dancing performed by contortionists.

The only blessing of this nightmarish experience was Rameau’s glorious music, especially in the hands of early music expert Teodor Currentzis. His tempi were occasionally idiosyncratic, and there was an excessive pianissimo in the opera’s most famous aria, “Tristes apprêts, pâles flambeaux,” but this was most likely to accommodate the soprano.

The star of the show was the Trinidadian soprano, Jeanine de Bique. Thanks to her stage presence, she was able to mesmerise the huge Palais Garnier with a mere glance. Despite her small voice, “Tristes apprêts, pâles flambeaux” was the highlight of the evening. At the end of the opera, she was allocated Planète’s aria “Fête de l’univers” where she dazzled with the sublime beauty of her voice and effortlessly natural style.

Jeanine de Bique (Télaïre) & Marc Mauillon (Pollux) in Opéra national de Paris’ Castor et Pollux. Photo: Vincent Pontet

In the 1737 version, Castor’s part is shorter, yet Belgian tenor Reinoud Van Mechelen made the most of it. Unfortunately, French bari-tenor Marc Mauillon was poorly cast in the role of Pollux. A darker voice is needed to convey the character’s nobility, and to contrast with Castor’s voice. French mezzo Stéphanie d’Oustrac as Phébé impressed with her memorable stage presence. Dramatically, she was the strongest in the cast, but vocally a disappointment; one wished the vocal fury were at par with the histrionics.

This is Sellars’ third consecutive production deemed by most to be a flop. The reviews of his most recent Beatrice di Tenda have been scathing. As I waited to hail a taxi to my hotel, a crowd of animated Parisians were vociferously arguing. A middle-aged man thought it was all very “cool.” Others sneered, and one young lady said “The contortionists were really impressive. Maybe Sellars should direct breakdancers and contortionists in the future. He seems to have a knack for that.”

L’Opéra national de Paris’ production of Rameau’s Castor et Pollux runs until Feb. 23 at the Palais Garnier. www.operadeparis.fr/en